Your Goal Broke the System

"Because I've done a lot of television, I'm sort of a generalist. I'm not a pastry cook, but I've had to learn a certain amount about it. I'm not a baker, though I've had to learn how to do it. I'm sort of a general cook." - Julia Child

I've been overthinking while trying to remember something I read or watched a few years ago that explained fourth-dimensional thinking and time travel. It involved looking directly at the tip of a pencil rather than seeing the entire pencil itself and I found it was a perfect analogy for how to think about "time."

Films such as 1997's Event Horizon and 2014's Interstellar have also explored a similar concept when they explain wormholes or 'folding space' (side note: watching these two scenes back to back is kinda funny how, err, similar they are):

To summarize:

A wormhole represents the idea of taking two distant points in space and bringing them together by folding space-time, creating a shortcut.

If I've kept your interest this long, you're probably already asking yourself, what on earth has been on my mind lately with all this talk of wormholes? And no, I'm not thinking about making a DeLorean.

We often think of time or goals as linear, but there's a more nuanced way to understand these concepts, like in the analogy of a pencil and wormholes. It's a bit of a reorientation towards systems instead of goals, combined with the need for more generalist thinking rather than expert knowledge.

We also think of life, progress, and knowledge in purely linear terms, as though we're moving down a single path toward a specific goal. But in reality, what if that path isn't a straight line at all, but rather, it's more like the space around a wormhole?

This analogy of focusing only on the tip, rather than seeing the entire pencil, perfectly captures how we often approach goals: we focus on one point and miss the more extensive system at play.

This reorientation can be observed all around us - even take a look at newer medical practices compared to traditional doctors. Functional medicine, for example, looks at overall health as a system, focusing on the root causes and interactions within the body rather than treating individual symptoms in isolation.

Looking at things as an ecosystem rather than diving deep into a specific goal has proven to be a valuable exercise. Rather than focusing only on an endpoint, what if you try to see the interconnections, loops, and cause-and-effect relationships—try to grasp the entire structure? Don't just aim for the 'tip of the pencil'; rather, strive to see and understand the entirety of how an overall system works.

This is often referred to as systems thinking. It's a practical approach that embraces things' complexity, interconnections, and non-linearity. It offers a more flexible and dynamic way of understanding and solving problems. When you're an expert and your focus is on a goal, your thinking becomes more linear and rigid. You concentrate on reaching specific targets without considering the broader system, which can be limiting and often has unseen side effects.

Just as seeing the entire pencil rather than its tip gives you the bigger picture, James Clear's Atomic Habits emphasizes systems thinking—focusing on the processes and habits behind success rather than fixating on the momentary achievement of a goal.

If you want to fix or change something long-term, you must invest in the system that creates/shapes the environment. Clear asserts that focusing on the processes and habits that lead to desired outcomes rather than fixating on the outcomes themselves can shift your mindset toward continuous improvement and adaptability.

"Achieving a goal only changes your life for the moment. That's the counterintuitive thing about improvement. We think we need to change our results, but the results are not the problem. What we really need to change are the systems that cause those results. When you solve problems at the results level, you only solve them temporarily. In order to improve for good, you need to solve problems at the systems level. Fix the inputs and the outputs will fix themselves. You do not rise to the level of your goals. You fall to the level of your systems." - James Clear

For example:

- Running a marathon is a goal; consistency around training is a system.

- Losing weight is a goal; eating healthy is a system.

- Learn the piano is a goal; spending an hour each evening watching YouTube videos and playing along is a system.

- Read 50 books per year is a goal; spending an hour reading every night before bed is a system.

Heck, this even applies every day to a software engineer: fixing a bug (or delivering a feature) is often rooted in the fact that you have a specific, narrowly defined goal. If you looked at the system, you'd focus on the structure, patterns, and relationships within a platform. Instead of simply fixing a bug, you want to step back and analyze how the architecture functions and develop a deeper understanding of how various components interact and how they contribute to the system's overall behavior.

You get my point.

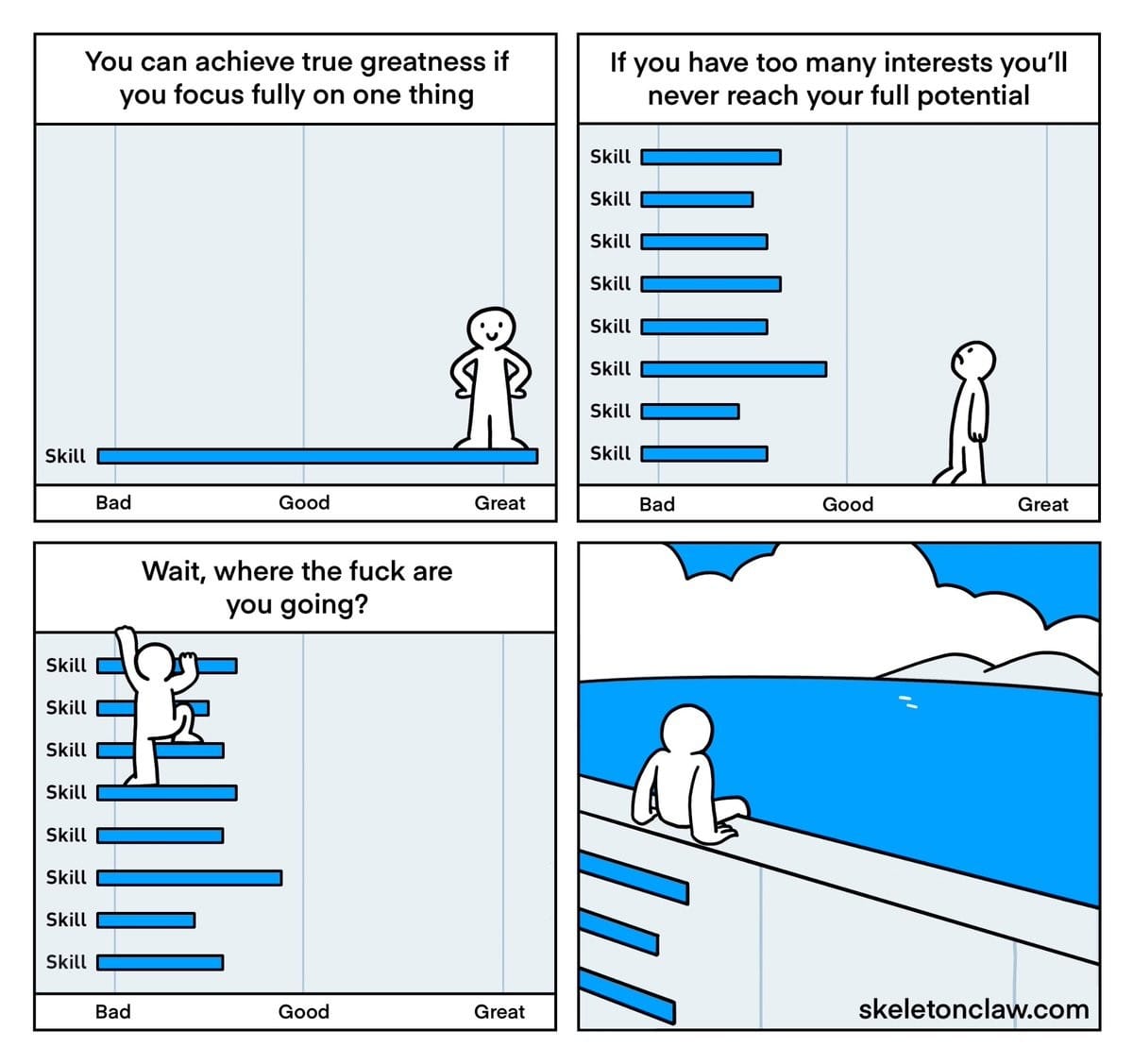

Now, I want to discuss the vital role that generalists play in systems thinking. In this context, generalists thrive because they see broader patterns across disciplines. While deeply knowledgeable, specialists may need to be more focused on specific goals or deep knowledge and nuance of only a part the system. Generalists emerge as the thinkers best equipped for navigating these complex, non-linear systems. They understand the relationships between disciplines, seeing not just the goals but the processes and structures that connect disparate things.

I wonder if we've become too focused on momentary goal-solving and overemphasizing that the only way to succeed is to create specialty experts. Of course, we need experts - obviously, I want my heart doctor to be an expert. Still, I've been finding that valuing generalist thinking is a valuable way to think differently about problem-solving.

I've seen a lot of chatter lately about the "rise of the generalist", and maybe this is why.

The concept of generalists can be a powerful force for adaptability and innovation, especially when you're exposed to tools like Generative AI, which allows me to become an "expert" in a deep topic quickly. For example, I don't need to know all the commands in git now, but I need to understand how it works relative to the ecosystem it's in.

Generalists are usually curious people who like to hop around from domain to domain. They enjoy figuring things out, especially in areas that are uncertain or new. They're good at solving problems that domain experts struggle with because they can bring bits of knowledge from diverse fields together. - Dan Shipper

And in David Epstein 's fantastic book, Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World, he claims:

"The challenge we all face is how to maintain the benefits of breadth, diverse experience, interdisciplinary thinking, and delayed concentration in a world that increasingly incentivizes, even demands, hyperspecialization."

Epstein argues that being an "expert" on something outside of a few areas:

"Seeing small pieces of a larger jigsaw puzzle in isolation, no matter how hi-def the picture, is insufficient to grapple with humanity's greatest challenges. We have long known the laws of thermodynamics, but struggle to predict the spread of a forest fire. We know how cells work, but can't predict the poetry that will be written by a human made up of them. The frog's-eye view of individual parts is not enough. A healthy ecosystem needs biodiversity."

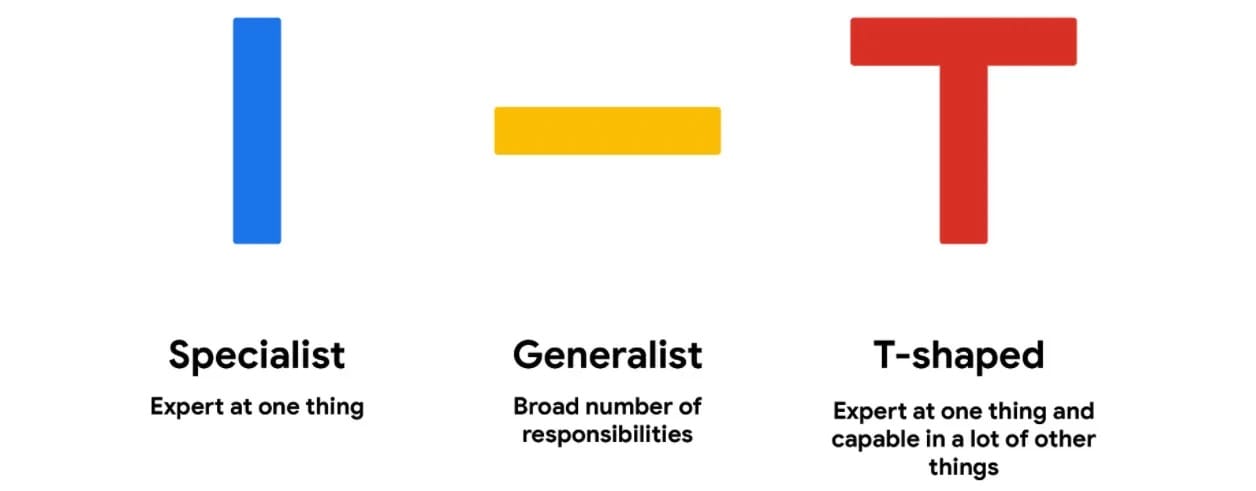

'Knowing a lot about one thing and a little about a lot of things' seems to be becoming a more powerful asset as we understand more about shapes of knowledge.

For example, a 'T-shaped' generalist has deep expertise in one area but is also broadly knowledgeable across other domains. This combination allows them to adapt and see connections across disciplines, much like understanding one part of a system helps you understand the whole.

The T-shaped generalist combines the best of both worlds (specialists and generalists). It's like someone who has mastered the guitar and can also play several other instruments proficiently. They possess a deep understanding of one engineering domain, much like their guitar-playing expertise. However, they are also familiar with other areas, ensuring they always recover when faced with different challenges.

I'm unsure if all this rambling makes sense or that I got my thinking across, but as we continue to face increasingly complex challenges, embracing generalist thinking and systems approaches seems to be a bit of an unlock for thriving in a world that demands both depth and breadth.

Amor Fati ✌🏻